Just a few years back, everybody was using wired earbuds. We were able to choose the ones that were most comfortable and offered the best sound quality. And we could walk through life blissfully unaware of the technology inside our earbuds. But then Apple released the iPhone 7. If your memory is a bit fuzzy, that’s the iPhone that eliminated the 3.5mm aux port. All of a sudden, Bluetooth headphones were no mere novelty. For Apple users, they had become a necessity.

Since then, Bluetooth headphones have become ubiquitous, as more and more Android users have also started using them. But this explosion of technology can easily become confusing. All of a sudden, we’re expected to learn a bunch of new terms. And, manufacturers being manufacturers, they oftentimes list these features as a series of acronyms. You may have seen some earbuds advertised as TWS, short for “true wireless stereo”. What does this mean? We’re here to give you a full explanation. But first, a little history lesson.

How Stereo Earbuds Used to Work

Wired earbuds utilize a 3.5mm aux jack. If you have a 3.5mm plug nearby, take a close look at it. You’ll see that it’s divided into three or even four segments. Each segment actually connects to a different wire inside the cord. A three-segment plug has a single segment connected to each earbud, with the third segment shared between the two. A four-segment plug offers a dedicated second segment for each earbud. The plugs are interchangeable. However, a four-segment plug will give you better quality if you’re plugging into a four-segment jack.

To make these earbuds work, a separate electrical current is pushed through each wire. Because the signals are separate, creating stereo sound is simple. All your device has to do is sent the left channel to your left ear, and the right channel to your right ear. The electric current runs through a wire coil inside each earbud. In turn, that coil drives a magnet, which oscillates behind a diaphragm. This assembly is commonly referred to as a driver. And the diaphragm is what actually produces the sound. It’s similar to the cone in a full-sized speaker, which moves back and forth to create sound waves in the air.

This technology has been around for decades, and is fairly standard. Take any 3.5mm wired headphones, plug them into any 3.5mm jack, and you’ll get sound. And if the recording is in stereo, you’ll get stereo. It’s simple and straightforward. Nobody ever needed to ask if their earbuds were stereo. You took it for granted. But then, Bluetooth was invented. And that changed everything.

The Birth of Bluetooth

Most of us think of Bluetooth as a late 90s or early 2000s technology. And that’s true to an extent. It’s when the technology first became popular. But the origins of Bluetooth go back a little further. The original design was actually created in 1989, by a team of engineers at Ericsson Mobile. Their goal was to create a short-distance radio protocol for pairing their phones with different devices. The team leader, Jaap Haartsen, was nominated for the European Inventor Award in 1999. Fun fact: the Bluetooth protocol is named for Harald Bluetooth, legendary king of Denmark and Norway. The Bluetooth logo actually consists of the old Norse runes for H (ᚼ), and B (ᛒ) laid over each-other.

| Year Introduced | Bluetooth Version | Feature |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2.0 | Enhanced Data Rate | 2007 | 2.1 | Secure Simple Pairing | 2009 | 3.0 | High Speed w/ 802.11 WiFi Radio | 2010 | 4.0 | Low-energy Protocol | 2013 | 4.1 | Indirect IoT Device Connection | 2014 | 4.2 | IPv6 Protocol for Direct Internet Connection | 2016 | 5.0 | 4x range, 2x speed, 8x message capacity + IoT |

Meanwhile, other inventors were collaborating on a different technology. In 1997, an IBM engineer named Adalio Sanchez was in charge of developing their new ThinkPad laptop. He wanted to integrate a cell phone into the new laptop. But while IBM had a lot of PC experts, they didn’t have any cell phone expertise. He reached out to Nils Rybeck, an Ericsson engineer, to see if the companies could collaborate. For almost a year, the companies tried to build a cell phone into a laptop. But at that time, there wasn’t a way to do this efficiently. The battery demands were simply too great, and using the phone would drain the laptop far too quickly.

But all hope was not lost. As it so happens, Rybeck was on the Bluetooth development team. He suggested to Sanchez that, rather than build a phone into a laptop, they use Bluetooth to connect the two devices. But they had another problem. Neither Ericsson nor IBM dominated their sector of the market. If they kept the technology proprietary, it would be useless to most people. You’d only be able to use it to connect an Ericsson phone to an IBM laptop.

To ensure that the technology was useful to everybody, the two companies agreed to make Bluetooth an open industry standard. Ericsson would maintain the rights to the Bluetooth radio technology itself, while IBM would develop the software logic. The companies reached out to teams from Intel, Toshiba, and Nokia to get the entire market on board. And in May, 1998, the standard was officially announced, with all five companies involved in the initial rollout.

The first Bluetooth device to hit the market was a mobile headset. It debuted in 1999, and won the “Best of Show Technology Award” at the COMDEX trade show in Las Vegas. However, there wasn’t any market for it. No-one had released a Bluetooth phone yet! The Ericsson T36, their original Bluetooth phone, ran into production issues and had to be scrapped. So it wasn’t until the 2001 release of the Ericsson T39 that a mobile phone actually supported Bluetooth. IBM followed shortly thereafter in October, 2001. Their ThinkPad A30 became the first PC with Bluetooth capability.

Early Bluetooth Limitations

As with all new technologies, the first version of Bluetooth had its share of hiccups. The various partners didn’t always agree on which features they needed. And since the protocol was being developed simultaneously with the first Bluetooth devices, not everything worked as intended. To use one example, some developers wanted to allow devices to connect anonymously. Since this feature didn’t make it into the original 1.0 release, several planned projects had to be cancelled or delayed.

The next release, 1.1, fixed a number of basic errors. But the biggest benefit was the addition of a received signal strength indicator (RSSI). This helped devices to maintain consistent pairing, even if the signal was not consistent. But many problems remained, particularly with interference from extraneous radio sources. This problem was fixed in Bluetooth 1.2, with the addition of adaptive frequency-hopping (AFH). AFH allowed devices to change frequencies on the fly. So if you were riding a commuter train, you wouldn’t lose your Bluetooth connection just because the train went past a cell phone tower. Another major improvement was the addition of Extended Synchronous Connections (eSCO). This solved an earlier problem where lost packets disappeared into the ether. Instead, dropped packets would be re-transmitted. As a result, sound quality became much clearer, with fewer choppy connections.

Better Profiles and Faster Data Transfer

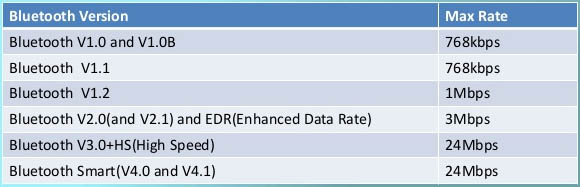

You’ll notice that we still haven’t said anything about earbuds. The reason is that nobody was thinking seriously about Bluetooth for high-quality audio. This first began to change in 2005, with the release of Bluetooth 2.0. This was a major upgrade, and the primary improvement was an increased data rate. While Bluetooth 1.2 was limited to data transfer rates of 721 Kbit/s, Bluetooth 2.0 allowed for a rate of 2.1 Mbit/s. To put that in perspective, 721 Kbit/s is very low quality, much like you’d expect from a bad landline. 2.1 Mbit/s is equivalent to 131 KPS, or roughly the standard 128 KPS MP3 bitrate. While MP3 was still a new technology, designers quickly grasped the implications.

But there was a problem. They could only send a single, mono signal. Remember how wired earbuds receive two separate signals, one for each side? That was not possible with Bluetooth. So even though Bluetooth earbuds were starting to become available, your music would only play in mono. Various attempts were made to improve the technology, including simulated stereo sound. But audiophiles could easily hear the difference between simulated and real stereo.

True Wireless Stereo

With further improvements to the Bluetooth protocol, it finally became possible to listen in stereo over Bluetooth. TWS technology gets around Bluetooth’s inherent restrictions by using a neat trick. It doesn’t send a separate signal to each earbud. That would still be way too complicated to engineer. But there’s another way.

Here’s how it works. Instead of sending the same signal to both earbuds, your device sends both channels to a single earbud. That earbud then plays its channel, while transmitting the other channel to the other earbud. So, for example, your phone would send the full stereo signal to the right earbud. The right earbud then divides that signal, and sends the left channel signal to the left earbud. As a result, you hear both channels as originally intended, just as you would with traditional headphones. Thanks to TWS, we now have the best of both worlds. The convenience of wireless earbuds, and the sense of space you get from stereo. Audiophiles around the world can rejoice.

Meet Ry, “TechGuru,” a 36-year-old technology enthusiast with a deep passion for tech innovations. With extensive experience, he specializes in gaming hardware and software, and has expertise in gadgets, custom PCs, and audio.

Besides writing about tech and reviewing new products, he enjoys traveling, hiking, and photography. Committed to keeping up with the latest industry trends, he aims to guide readers in making informed tech decisions.