When you’re shopping for audio equipment, it can sometimes be difficult to understand what you’re actually buying. Many manufacturers are crystal clear about what they’re selling, but others simply assume you know all the latest industry terms. As a result, a lot of product listings read like a technical spreadsheet. The wall of jargon can get confusing, especially if you don’t spend half of your time reading up on audio equipment.

We can’t clear up everything for you, at least not all at once. But today, we’re going to demystify one of the most common terms you’ll see: aptX Low Latency. This is a common audio codec, which is becoming more and more popular. But what separates it from the competition? Is it a good value? Or are these manufacturers just blowing smoke? We’ll take a deep dive, and explain everything you need to know.

What is a Codec?

Before we talk about aptX in particular, it’s important to define some terms. So, what is a codec to begin with? Back in the old days, audio was analog. Think of a vinyl record. The grooves in the record exactly record the audio, with no loss of data. This is why many musicians, even today, release their albums on vinyl along with MP3 offerings.

With the advent of computers, it became necessary to store audio as a series of 1s and 0s. However, this process isn’t 100 percent accurate. And the more accurate you want your recording, the more disc space it’s going to take up. For the sake of efficiency, software developers invented what’s called a coder-decoder, or a codec for short. The coder part of the software encodes the analog audio. It usually uses a variety of techniques to compress the data as much as possible. The decoder part of the software reverses the process, turning the compressed audio into a usable signal.

Whether you realize it or not, you use codecs every day. For example, streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon compress their video and audio. If they didn’t, you’d need an ultra-high-speed fiber-optic connection just to watch a movie in 720p. Codecs are also used for MP3 files, home video, and even phone calls. As a matter of fact, codecs have been used for phone calls since the middle of last century.

Loss vs. Latency

When choosing a codec, you need to balance two different features: loss and latency. Succinctly, loss is the drop in quality from the original analog signal to the decoded digital output. Latency is the delay between receiving the data and playing it. So, why is there a trade-off?

The reason is that all codecs involve some level of loss. If they didn’t, they’d just be an analog signal. But some codecs are more lossy than others. For example, MP3 files typically only take up a few megabytes. So-called “lossless” FLAC files can be up to 10 times as large. The smaller the file size, the more lossy the file. Lossless codecs are usually used by professionals. You’ll never see a studio producer or movie studio using MP3 files for production or editing. More lossy codecs are generally used by consumers. You can buy some music in FLAC format, but most music is sold in MP3 format.

Lossier codecs are also used for streaming and phone calls. The reason for this should be apparent. If you wanted to stream a movie in a lossless format, you wouldn’t be able to do it live. You’d have to wait all afternoon just to buffer an episode of Stranger Things.

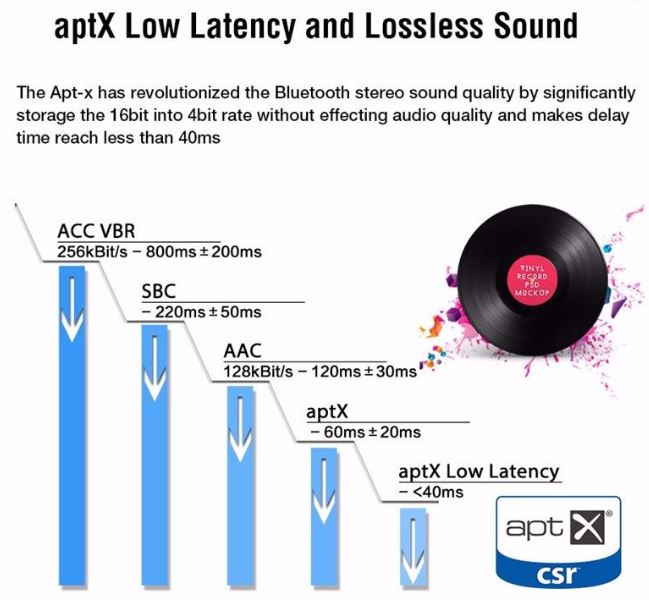

Latency is related to loss, because your decoder – for example, your wireless earbuds – needs time to decode the audio. The larger the file, the longer it will take to decode. This leads to a small amount of delay. Now, for many purposes, latency is irrelevant. If you’re listening to music, you won’t know or care that a song starts 100 milliseconds after you press “play”. But it can become a serious irritation when you’re watching a movie or TV show. If your latency is greater than about 50 milliseconds, you’ll notice that the audio is behind the video. For these purposes, a low latency codec is essential.

What is aptX?

In 1973, scientists at Bell Labs developed a newer, more efficient codec for transmitting vocals. It was called Adaptive differential pulse-code modulation (ADPCM). Without getting too far into the weeds, it allowed for more accurate transmission of audio over the phone. Early wireless headphones also used this standard. However, when used for music, ADPCM has significant limitations. It uses a technique called psychoacoustic auditory masking, which means that it doesn’t actually keep as much of the signal as you’d think. It does this by “tricking” your ears into hearing tones that aren’t present. But this technique isn’t equally effective on all people, and it’s definitely not as effective as a fuller signal.

By the early 1980s, a solution was already on the way. A Queen’s University student named Stephen Smyth developed the aptX codec as part of his Ph.D. research. This codec was designed to use most of the same principles as ADPCM, without the need for psychoacoustic auditory masking. Of course, in these days, wireless headphones weren’t widely available. The original aptX codec was used by broadcasters, who needed something less lossy than ADPCM. aptX allowed them to store CD-quality audio on a hard drive, reducing the need to juggle CDs for frequently-payed segments.

This was a niche market, and it wasn’t clear whether or not aptX would ever be used for anything else. However, the codec got a huge boost when Disney decided to start using it in the 1990s. Previously, they’d needed to fly actors in to their studios for voice dubbing. With aptX, they were able to transmit the audio via ISDN lines, all the way from Europe to Los Angeles. aptX was the first codec that was high-enough quality to allow for this kind of transmission.

While 1990s Disney wasn’t the massive media behemoth that it is today, it was still a high-profile entertainment company. More importantly, they specialized in animated films, with an emphasis on quality voice acting and singing. If aptX was good enough for the people who made Beauty and the Beast, the thinking went, it would be good enough for other companies. aptX spread like wildfire, becoming widespread in the film, television, and radio industries. More recently, it became the default codec for VoIP providers such as Vonage.

However, aptX was too demanding for early Bluetooth audio systems. These systems still used an older codec called SBC, which is short for sub-band coding. SBC requires fewer system resources than aptX, but it’s more lossy. But in recent years, the Bluetooth protocol has become far more capable. And the small circuits in wireless earbuds became more advanced. As a result, many current earbud manufacturers are using the aptX codec for clearer, higher-fidelity audio.

The technology itself has been owned by a variety of companies over the years. The original buyer was Solid State Logic, in 1988, which later became Carlton Communications. Carlton themselves split in 2009. From there, aptX has gone through a series of owners. Since 2015, the licensing rights have been owned by Qualcomm.

What is aptX Low Latency?

While aptX has always been less lossy than the alternative, that’s come with a downside. Earlier aptX codecs took a long time to decode, as much as 100 milliseconds. This wasn’t a big deal if you were a radio broadcaster. Nor was it a problem for entertainment companies. Who cared if your audio track had 100 milliseconds of latency? You could always fix it in editing.

The same is not true for home video. If you’re watching a movie and the audio track is 100 milliseconds behind the video, you’re definitely going to notice. To address this, Qualcomm sought to expand the codec’s capabilities. After acquiring the licensing rights, they developed two additional versions of the aptX protocol: aptX HD, and aptX Low Latency. aptX HD is designed for “better-than-CD high definition sound quality”. It’s high latency, but because of its rich profile, it’s the codec of choice for listening to lossless FLAC files.

aptX Low Latency, on the other hand, has been designed for a maximum of 40 milliseconds of latency. If you remember what we said earlier, you’ll know that this is a short enough delay that it’s not noticeable. It’s slightly more lossy than standard aptX, but only the most dedicated of audiophiles will notice the difference. Qualcomm has also recently announced a third new codec called aptX Adaptive. aptX Adaptive ensures low latency, but switches to less lossy versions of the codec when there’s a stable enough connection. We haven’t seen any earbuds with this feature – yet – but it’s on the way.

One other thing we should note is that at this time, iPhones don’t support the aptX codec. They’ve been focusing instead on their own exclusive codec, W1. As a result, aptX Low Latency earbuds won’t improve your experience on iOS devices.

Meet Ry, “TechGuru,” a 36-year-old technology enthusiast with a deep passion for tech innovations. With extensive experience, he specializes in gaming hardware and software, and has expertise in gadgets, custom PCs, and audio.

Besides writing about tech and reviewing new products, he enjoys traveling, hiking, and photography. Committed to keeping up with the latest industry trends, he aims to guide readers in making informed tech decisions.

Excellent narration on the things to a layman. Got lot of information on the things and its evolution. i was on the way for googling aptX ll. thank you for this account.

Hi, read your article with interest and it did clarify matters somewhat. I am looking to buy some aptx LL earbuds ( as a spectaclesingle wearer I find overeat phoneso uncomfortable ) but finding very difficult to find any. Lots with aptx but none specifying LL

I understand that you may be constrained in your position but if you could point me in the right direction regarding appropriate brands /models I would be most obliged.

Thanks in anticipation,

Regards Mike.

Thanks, I finally understand what Aptx does.

Hi author,

Good explanation, however if it is lossier than standard aptX and how the reduction in latency will improves the music quality? How even audiophiles notice improved sound quality otherthan syncing due latency improvement.

How this codec will improve the HD sound quality compared to LDAC, aptX HD etc.

Great article. Thanks,

Thanks a lot for this detailed explanation. I need to resolve my problem badly, suffering as I have been with a non Bluetooth TV and needing low latency earbuds to assist with my hearing without a latency penalty. Need to find the right product now and do not know whether or not you are able to recommend the best around.

If you can, I would be grateful. Technology is not my strong suit but I am trying hard to keep up with a fast moving technological world.

Appreciate your skills. At over 80, a little late for me to become a genius in this ever- changing field.

Thank you so much for such an insightful article! This reminded me of what the internet used to be like in it’s early days when there were so many of these types of articles.

A couple of years ago I was looking for a low latency option that would allow me to monitor audio from my video camera while filming and it was as a result of aptX Low Latency that I was able to accomplish that objective. Someone asked about it recently and I wanted to offer some additional details which is how I came upon your article.

Much appreciated.